A friend and I were having a conversation about Michael Jackson and his life’s work and the song, lyrics and the short film Black or White came up in discussion. Both of us grew up in the sixties and our dialogue covered most of the relevant issues and the discussion went on for hours. I brought up Stevie Wonder’s equivalent “Ebony and Ivory.” She remembered. We spoke of The Black Panthers, Abbey Hoffman, Reverends Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson and Michael’s childhood during the turbulent civil rights movement. We spoke of the riots in Chicago, Viet Nam and the Peace Movement and flower children. I recall those days with a wistfulness that I am not able to explain in words. It’s a feeling. I wish I could share it with you; it’s not possible.

A friend and I were having a conversation about Michael Jackson and his life’s work and the song, lyrics and the short film Black or White came up in discussion. Both of us grew up in the sixties and our dialogue covered most of the relevant issues and the discussion went on for hours. I brought up Stevie Wonder’s equivalent “Ebony and Ivory.” She remembered. We spoke of The Black Panthers, Abbey Hoffman, Reverends Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson and Michael’s childhood during the turbulent civil rights movement. We spoke of the riots in Chicago, Viet Nam and the Peace Movement and flower children. I recall those days with a wistfulness that I am not able to explain in words. It’s a feeling. I wish I could share it with you; it’s not possible.

At some point the phone heated up on my end as I realized that my friend had just gone through some fresh and still stinging criticism for speaking about the history within Michael Jackson’s work. Her outburst had raised the ugly issues of racism and white guilt. And though she could speak with me about it, she was just too weary to address it in ways I had previously suggested—like writing it, teaching classes or a podcast where we, black and white, could discuss racial issues and how it had affected us growing up. When I brought it up once again, her voice cracked and got soft as she said: “I can’t. I lived it and I’ve paid my dues. I can’t pay them again.” There was such a complete and utter resignation in her voice, such a morbid weariness! I completely understood. But part of me got really angry as the tears in my throat stung silent and sad.

My friend holds a rich piece of history that may never be shared. You see, she is black. African American. Negro. And she’s been a lot of those other things that people say to differentiate a shade of skin color, some of them not polite. She can’t tell you the stories because when she brings up the subject some say she is rehashing a past that is irrelevant now or that she has a secret agenda behind her words. So you get the history lesson here; indulge me and permit the white girl to tell you…

I lived that same past and my stories too, could make your hair stand at attention, and there is a weariness now when those days are revisited. It’s hard to describe but it’s like donor fatigue. When people give and give until they are empty and still they know that more is needed but are c ompletely tapped out—not just of money, but energy. Been there.

ompletely tapped out—not just of money, but energy. Been there.

Some children are born with a sensitivity and with an innate sense of justice and right and wrong. I was such a child; Michael Jackson was such a child and my daughter is one. They know when something is deeply offensive to the human being—because the internal radar signals an alarm. Injustices can be subtle like the “driving while black” (DWB instead of DWI) that means you are more likely to be stopped and ticketed by a police officer—especially if you are driving a luxury car or sports car. Officers who stereotype see a black person in a car they don’t belong in and immediately assume they are criminal. And it’s worse when it happens in a mostly white and affluent neighborhood. It’s called racial profiling. It wasn’t so subtle back then and “politically correct” didn’t exist. Racism and sexism were not closeted then.

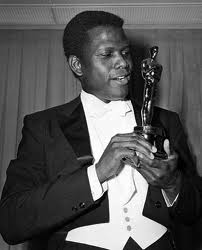

During the sixties and seventies, racial profiling was so common that there was no name for it because it wasn’t considered out of the ordinary. That is, until black folks started pointing it out. It wasn’t limited to driving—it was so pervasive that it was like “being… while black.” Skin color was noticed. Distinctions were even made about “light skinned blacks” and they were more acceptable than their darker brothers. Interracial couples were harassed and mixed marriages were frowned upon. “To sir with Love” a movie released in 1967, featuring Sidney Poitier helped to soften the stigma.

During the sixties and seventies, racial profiling was so common that there was no name for it because it wasn’t considered out of the ordinary. That is, until black folks started pointing it out. It wasn’t limited to driving—it was so pervasive that it was like “being… while black.” Skin color was noticed. Distinctions were even made about “light skinned blacks” and they were more acceptable than their darker brothers. Interracial couples were harassed and mixed marriages were frowned upon. “To sir with Love” a movie released in 1967, featuring Sidney Poitier helped to soften the stigma.

I never had to worry about “being while black” or trying to make myself harmless or invisible or to keep pushing down my justifiable DNA-cellular rage, like a beach ball underwater. I didn’t have to keep my radar on high alert or scan my environment in perpetual motion to feel the vibe for safety and test if I was too presuming or if just my presence alone put me in jeopardy. I can tell you stories of racism from both sides—back and white. And red. My partial Native American heritage is testament to my ancestors similarly turned into non-humans and called savages, which is every bit as hurtful as the N-word. But I can pass for completely white because I look Anglo. My son, when he was younger and tanned in the summer was called “Indian” or sometimes “chief.”

I confided to her that I loved not just music, but dance. I remember that while Dick Clark’s American Bandstand was exciting, Soul Train was the happenin’ place. (For the younger crowd- Bandstand was a kind of virtual music and dance club for white kids on after school TV, but Soul Train was the rockin’ black version.) So the natural progression for me—a blues, soul, and funk music and dance addict, was to find my way to the reality version of Soul Train, which meant the clubs on the north side of Milwaukee and the south side of Chicago. Many times I was the only white girl in the place.

I confided to her that I loved not just music, but dance. I remember that while Dick Clark’s American Bandstand was exciting, Soul Train was the happenin’ place. (For the younger crowd- Bandstand was a kind of virtual music and dance club for white kids on after school TV, but Soul Train was the rockin’ black version.) So the natural progression for me—a blues, soul, and funk music and dance addict, was to find my way to the reality version of Soul Train, which meant the clubs on the north side of Milwaukee and the south side of Chicago. Many times I was the only white girl in the place.

So I understand my friend’s transverse fatigue. I lived it too but not in the same way. It’s hard to understand prejudice unless you have walked in those shoes, or in my case, the white girl with moccasins. The intolerance shown my friend for her grandmotherly, archetypal wisdom is an affront that just simply cannot stand. We need to acknowledge and honor all those who came before. Remember Michael’s tribute to Sammy Davis Junior? It was homage to his paving the way so Michael might follow. And Michael paved the way so that others might follow.

The past and Michael Jackson’s part in it, his contribution to the present and impact on the future, is not to be understated or dismissed. Not by me—and now not by you. Nor will it be made irrelevant on my watch by the ignorance in that glaring vacuum of knowledge crushing the spirit of my friend. Jackson’s life and how he lived it, how he and his life were shaped by the times in which he and we lived, and how that influence helped him shape the future is very relevant to understanding Michael, the man. It is also an essential piece of how Michael’s aesthetic informs his work.

Historical context in the work and aesthetic of Michael Jackson is everything. The Rodney King incident in Los Angeles that made headlines around the world and caused riots and racial tensions occurred in March of 1991. Michael Jackson’s Black or White with it’s obvious silent commentary was released in November of the same year. It’s important to remember that. Rodney King was a seminal moment in black history. African Americans had been complaining for a long time about racial profiling and police brutality and it was summarily dismissed and laughed off. During the Rodney King incident, a covert videographer taped a group of white police officers severely beating a black man who offered no resistence putting him in the hospital. Those officers, when tried in court in LA were acquitted triggering the LA riots.

Those younger fans or the newcomers to the MJ party can fully appreciate Michael Jackson’s work when his courage, his boldness and the depth of his love for humanity is fully comprehended. It was his stealth that saved him much because to out overt racism was politically incorrect; it was his boldness and the silent screams that made him a target for those who awoke to what he was doing.

To put some perspective on the times: The Vietnam War was ongoing and Kent State was fresh in the collective memory. At Kent State, protesting university students had been shot and killed by the National Guard, an incident which pitted a generation of idealistic youth against their own government. John Lennon was on the FBI “watch” list for being a ‘peacenik” and “troublemaker.” There was an attempt to deport him and ban him from the United States. Michael was on lists that we may never hear about and never know.

To put some perspective on the times: The Vietnam War was ongoing and Kent State was fresh in the collective memory. At Kent State, protesting university students had been shot and killed by the National Guard, an incident which pitted a generation of idealistic youth against their own government. John Lennon was on the FBI “watch” list for being a ‘peacenik” and “troublemaker.” There was an attempt to deport him and ban him from the United States. Michael was on lists that we may never hear about and never know.

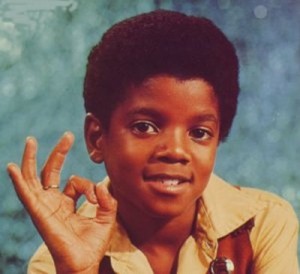

Michael Jackson was a civil rights activist. A freedom fighter. Michael, the Jackson Five and the Jackson family grew up in troubled and racially charged times. Prejudice was prominent and permanent and the black man (meaning the collective race) was a second class citizen. Much of the south was still segregated when Michael was born— black people had to stick to their own kind in schools, neighborhoods, public places, and even rest rooms. The doors of restrooms invited “colored” to separate and frequently sub-standard facilities. Black entertainers like Sammy Davis Junior, Little Richard, Louis Armstrong and others were tolerated and a bit more acceptable because of their talent, but often had to come in through the kitchens and garages of fine hotels and public venues because the front door was off limits to “coloreds.”

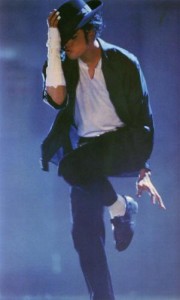

You may recall hearing that MTV refused to play Michael Jackson’s music video short films simply because he was African American. Michael single-handedly broke that barrier and I have to wonder if it is behind the question he asked when he won his second Grammy: “Can you hear me now?” That may have been meant for the blacks in the audience as much as the music industry itself. And Michael’s work was bold. After “Thriller,” Michael made “Bad” to be relevant and to give African Americans the message that they could and should go to college and that being bad as in educated, was good and relevant to them too. And in Black or White, Michael not only takes on prejudice in America, but in the whole world.

Black or White is a video that is filled with symbolic imagery and hidden messages. The Ghosts video has a startling reference to the Klan with its burning torches and marching mobs but it’s more subtle. Black or White took it on in full view and in living Technicolor. It was Michael Jackson in-your-face illustrating defiance against that reality of being black in America—that one was a target for violence at the hands of those who wanted you to “know your place” in the social hierarchy. As a black you understood that you were considered a bottom-feeder. Anything and anyone who advanced the race would likely become a target. It served the ego, prejudice and economics for blacks to remain second class citizens. White supremacy wasn’t just an idea; it was a reality. Michael Jackson’s aesthetic and work helped to change the minds and hearts of a generation but not without conflict. He was both beloved and hated; he received both affectionate accolades and death threats. And Michael absolutely understood that in order to keep his pulpit for social change, he needed to stay bold and controversial to maintain his relevance. His courage in music as a message is unparalleled.

Black or White is a video that is filled with symbolic imagery and hidden messages. The Ghosts video has a startling reference to the Klan with its burning torches and marching mobs but it’s more subtle. Black or White took it on in full view and in living Technicolor. It was Michael Jackson in-your-face illustrating defiance against that reality of being black in America—that one was a target for violence at the hands of those who wanted you to “know your place” in the social hierarchy. As a black you understood that you were considered a bottom-feeder. Anything and anyone who advanced the race would likely become a target. It served the ego, prejudice and economics for blacks to remain second class citizens. White supremacy wasn’t just an idea; it was a reality. Michael Jackson’s aesthetic and work helped to change the minds and hearts of a generation but not without conflict. He was both beloved and hated; he received both affectionate accolades and death threats. And Michael absolutely understood that in order to keep his pulpit for social change, he needed to stay bold and controversial to maintain his relevance. His courage in music as a message is unparalleled.

The times Michael grew up in were ripe for his arrival on the youthful scene. It was time for change. From the 1940s until the protests of the 1960s, entertainment had featured characters like: Little Black Sambo, Bosko and Inki which solidified the stereotypes of blacks in the minds of audiences. Hollywood prescribed and perpetuated the stereotype of black people as being non-human by featuring African American performers in cartoon caricature. People like Cab Calloway, “Fats” Waller, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters, Bill “Bo jangles” Robinson served as archetypes for a host of animals (yes animals) and people in animated features. This slanted depiction of blacks served to reinforce the animalistic and primitive (because of the natural affinity for dance and rhythms) nature of black folk. They were considered tribal and inferior.

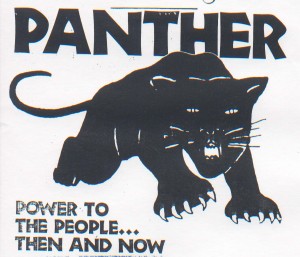

Until the 1960s, blacks being subjected to ridicule and stereotype was the cultural norm. The Black Panther Party was a political revolutionary movement that began in 1966 and lasted until 1975. It expanded to a social and cultural revolution with contemporary symbols like the closed fist. The “Afro” hairstyle became a symbol of the African American pride initiative begun by the Black Panthers and punctuated by James Brown in “I’m Black and I’m Proud” released in 1968. Michael publicly declared his allegiance to James Brown as the artist who influenced him most.

In a progression of television programs, the ingrained stereotype was diffused over time. The cutting edge childrens programs that Michael grew up with included Josie and the Pussycats, the Harlem Globetrotters and the Kid Power series which featured a cultural diverse group of eleven children. Kid Power’s theme and premise was that multiracial and multicultural kids who worked together collectively had the power to change the world socially and politically. The idea of Kid Power reflected concepts of participatory democracy and bottom-up social movements of the 1960s and 1970s that emphasized ideals like: Black Power, Brown Power, Red Power, Woman Power, and Power to the People. The series’ theme song “Kid Power… Red, Yellow, Black, and White…White, Yellow, Black, and Red… in other words, “It’s up to Kid Power …”

Michael watched and grew up with Kid Power—the program and the cultural message. Michael truly did believe that the power to change the world lies silent and untapped within children. The Kid Power message and influence explains his loyalty, affection and attention to children. He believed in youth. And it was in a unique time that Michael Jackson wove his magic into the social tapestry of his life and our history. Who Michael was, and what he contributed to civil rights in the social and cultural fabric was relevant then and deserves to be celebrated today. While Dr. King said it in words and actions, Michael Jackson said it in music, lyrics and the images of film. Michael Jackson, like Martin Luther King before him, was a prolific and vocal freedom fighter.

Michael watched and grew up with Kid Power—the program and the cultural message. Michael truly did believe that the power to change the world lies silent and untapped within children. The Kid Power message and influence explains his loyalty, affection and attention to children. He believed in youth. And it was in a unique time that Michael Jackson wove his magic into the social tapestry of his life and our history. Who Michael was, and what he contributed to civil rights in the social and cultural fabric was relevant then and deserves to be celebrated today. While Dr. King said it in words and actions, Michael Jackson said it in music, lyrics and the images of film. Michael Jackson, like Martin Luther King before him, was a prolific and vocal freedom fighter.

(C) B. Kaufmann 2010

6 Comments

OK… I’m needing to ponder what you just wrote here. WOW! I’ve read words similar to this before, but I’m visualizing and absorbing the meaning of your words for the first time with clarity. I will comment again after I ponder and read again. What you say can’t be read just once and completely understood; unless of course one has lived it. In the mean time, thank you so very much for your insight on this topic. I certainly could never imagine experiencing what you describe here. I was a child of the 60’s and 70’s, so I remember what it was like, but I truly have never experienced it. I’m really speechless. Thank you. I think more people need to read this.

This becomes very interesting because there are things I have not completely understood. For example I always wondered why Michael at the end is a panther and that ritual dance where he breaks up the racist messages in the car. And I have not understood what means the boy’s rebellious to the authority of his father who is catapulted into “another dimension” within his own planet in this case the wild Africa. This is starting to take shape, I´m waiting the second part. Thanks Barbara.

Thank you for reminding me of that crucial period in history. I lived on another continent, with different attitudes, though racism reared its ugly head now and again. Watching newsreels from America left me feeling sad and confused. 1967, my first real boyfriend, black and beautiful, and dear god how proud was this young white girl walking at his side! We were crazy in love, but always aware of certain people watching us. You were ever on your guard, waiting for a snide remark. Michael was a hero not only for his own race but to every one of us who were truly colour blind. Tempestuous and amazing times! I am glad to have lived through them, it did so much to shape who I am.

“Michael Jackson, like Martin Luther King before him, was a prolific and vocal freedom fighter.” Thank-you.

“You go Girl”. I also understand where your friend is coming from. Michael evolved from racism and exposed its injustice through the way he managed his fame, which he used to illuminate the world. Can’t wait for the next episode! Thanks.

Oh he was most definitely a Master Teacher (still is,) and most definitely divinely sent. Finally, the world is waking up to this. Little by little. And for the record Reverend Barbara, not on my watch either.